I offer the following post as my own contribution to the Madeline Kahn Appreciation hosted by, well, me. I do so as a roundabout way of acknowledging the fact that Madeline Kahn played no small part in making me the actressexual that I am today. (Blame it on Kahn's long creative collaboration with The Muppets.) So, when Criticlasm mentioned his appreciation of Kahn's final screen performance, I knew I need to take the time to see...

I offer the following post as my own contribution to the Madeline Kahn Appreciation hosted by, well, me. I do so as a roundabout way of acknowledging the fact that Madeline Kahn played no small part in making me the actressexual that I am today. (Blame it on Kahn's long creative collaboration with The Muppets.) So, when Criticlasm mentioned his appreciation of Kahn's final screen performance, I knew I need to take the time to see...

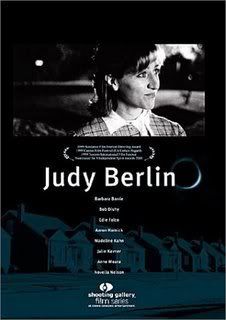

...Madeline Kahn in Judy Berlin (1999)

approximately 20 minutes and 41 seconds

15 scenes

roughly 22% of film's total running time

At first blush, Kahn's Alice seems to be the sort of woman who never knew a silence she couldn't fill.

At first blush, Kahn's Alice seems to be the sort of woman who never knew a silence she couldn't fill. Her fanciful riffs and sentimental musings -- all delivered in Kahn's distinctive staccato soprano -- are dense with private jokes, whimsical memories, and melancholic vulnerabilities.

Her fanciful riffs and sentimental musings -- all delivered in Kahn's distinctive staccato soprano -- are dense with private jokes, whimsical memories, and melancholic vulnerabilities. Yet as Alice uses her words to reach out to her beloved men, her chattery monologues serve only to deepen the very chasm they aim to bridge, with both her husband and son recoiling from the touch of Alice's voice. (Even the Golds' housekeeper Carol has learned to leave the vacuum cleaner turned on when Alice enters the room.)

Yet as Alice uses her words to reach out to her beloved men, her chattery monologues serve only to deepen the very chasm they aim to bridge, with both her husband and son recoiling from the touch of Alice's voice. (Even the Golds' housekeeper Carol has learned to leave the vacuum cleaner turned on when Alice enters the room.) The central event of Eric Mendelsohn's pensive film is a midday solar eclipse. This cosmic disruption to the daily order of things (aided by Jeffrey Seckendorf's luminous cinematography) also transforms the ordinary landscape of this ordinary suburb into something suddenly extraordinary. And for Mendelsohn, whose style of storytelling seems steeped in the style of Woody Allen's comic tragedies of domesticity, this eclipse operates as a narrative device for his characters to encounter previously unseen corners of their own hearts. During the eclipse Alice's husband and son undertake parallel, vaguely romantic encounters with, respectively, a prickly schoolteacher and her exuberant daughter. In contrast, Alice's eclipse odyssey is largely a solitary one. As she explores the newly unfamiliar streets of her neighborhood, Alice amuses herself with a running, unfunny joke about being a space man walking the moon.

The central event of Eric Mendelsohn's pensive film is a midday solar eclipse. This cosmic disruption to the daily order of things (aided by Jeffrey Seckendorf's luminous cinematography) also transforms the ordinary landscape of this ordinary suburb into something suddenly extraordinary. And for Mendelsohn, whose style of storytelling seems steeped in the style of Woody Allen's comic tragedies of domesticity, this eclipse operates as a narrative device for his characters to encounter previously unseen corners of their own hearts. During the eclipse Alice's husband and son undertake parallel, vaguely romantic encounters with, respectively, a prickly schoolteacher and her exuberant daughter. In contrast, Alice's eclipse odyssey is largely a solitary one. As she explores the newly unfamiliar streets of her neighborhood, Alice amuses herself with a running, unfunny joke about being a space man walking the moon. As Alice experiences the eclipse, first with her housekeeper and then a neighbor and finally alone, Kahn's performance quietly reveals that Alice's melancholy estrangement from her husband and son might be more complicated than anyone yet knows. Mendelsohn's screenplay charts Alice's character arc through her struggle to remember the final lines of a nursery rhyme (a poem which, not insignificantly, rhapsodizes about unknowability and age). Recitation after recitation stalls at the same line and no on seems to have any idea what poem she's talking about. Only when Alice is walking alone in the silence of the eclipse do the poem's final lines arrive to her and, with them, a quiet clarity. Here, Kahn's particular gifts as a performer suit the subtle challenges presented by the role of Alice. In particular, Kahn's verbal agility -- a tippling voice capable of astounding precision and dexterity -- coupled with the comedienne's veiled vulnerability make Alice a haunting and moving figure.

As Alice experiences the eclipse, first with her housekeeper and then a neighbor and finally alone, Kahn's performance quietly reveals that Alice's melancholy estrangement from her husband and son might be more complicated than anyone yet knows. Mendelsohn's screenplay charts Alice's character arc through her struggle to remember the final lines of a nursery rhyme (a poem which, not insignificantly, rhapsodizes about unknowability and age). Recitation after recitation stalls at the same line and no on seems to have any idea what poem she's talking about. Only when Alice is walking alone in the silence of the eclipse do the poem's final lines arrive to her and, with them, a quiet clarity. Here, Kahn's particular gifts as a performer suit the subtle challenges presented by the role of Alice. In particular, Kahn's verbal agility -- a tippling voice capable of astounding precision and dexterity -- coupled with the comedienne's veiled vulnerability make Alice a haunting and moving figure. Kahn's Alice knows that her husband is becoming lost to her or -- perhaps more frighteningly -- vice versa. And though the film never answers the question of whether or not this intimate estrangement is due to middle-class-middle-age malaise or something more ominous (like Alzheimer's or mental illness), Kahn's performance itself provides the simple cues that Alice knows that she's on the verge of disappearing -- of forgetting or losing touch with the reality she has shared with her family and community. As I read Madeline Kahn's performance, I see her Alice as a woman who knows that she's losing touch (think of the way she privately fumes when her neighbor penetrates her reverie with a reminder of something she's forgotten) whether through Alzheimer's or some other mental change. Further, Kahn's Alice seems to understand that the one person who might help maintain her connection to this world is her husband, Arthur, a man as terrified of the changes in his wife and son as he is of those in himself. It seems to me that Kahn's Alice alone appreciates the gravity of this estrangement, especially as the eclipse heightens Alice's lucidity about her stark circumstances.

Kahn's Alice knows that her husband is becoming lost to her or -- perhaps more frighteningly -- vice versa. And though the film never answers the question of whether or not this intimate estrangement is due to middle-class-middle-age malaise or something more ominous (like Alzheimer's or mental illness), Kahn's performance itself provides the simple cues that Alice knows that she's on the verge of disappearing -- of forgetting or losing touch with the reality she has shared with her family and community. As I read Madeline Kahn's performance, I see her Alice as a woman who knows that she's losing touch (think of the way she privately fumes when her neighbor penetrates her reverie with a reminder of something she's forgotten) whether through Alzheimer's or some other mental change. Further, Kahn's Alice seems to understand that the one person who might help maintain her connection to this world is her husband, Arthur, a man as terrified of the changes in his wife and son as he is of those in himself. It seems to me that Kahn's Alice alone appreciates the gravity of this estrangement, especially as the eclipse heightens Alice's lucidity about her stark circumstances. When I think of Kahn's performance Alice, I think of a balloon slowly descending to the ground: she begins all silly and exciting, bouncing at the corners of the ceiling, but as the movie unfolds her buoyancy diminishes and she comes close to touching the ground. Yet her lightness remains.

When I think of Kahn's performance Alice, I think of a balloon slowly descending to the ground: she begins all silly and exciting, bouncing at the corners of the ceiling, but as the movie unfolds her buoyancy diminishes and she comes close to touching the ground. Yet her lightness remains. Madeline Kahn's work in Judy Berlin is gorgeous in its simplicity and humanity. Alice has little of the galvanic potency of Barbara Barrie's brittle schoolteacher; nor does Alice burst with the exuberant faith of Edie Falco's Judy. Yet Kahn's Alice moors the emotional arc of the whole film with a wit, a poignancy and a stability that is transcendent. It's a sublimely discreet performance, ripe with mystery and teeming with humor: a moving exit for one of the greater actresses at the edges of the 2oth century.

Madeline Kahn's work in Judy Berlin is gorgeous in its simplicity and humanity. Alice has little of the galvanic potency of Barbara Barrie's brittle schoolteacher; nor does Alice burst with the exuberant faith of Edie Falco's Judy. Yet Kahn's Alice moors the emotional arc of the whole film with a wit, a poignancy and a stability that is transcendent. It's a sublimely discreet performance, ripe with mystery and teeming with humor: a moving exit for one of the greater actresses at the edges of the 2oth century.Blessings, dear Madeline.

6 comments:

Yay.

"I think of a balloon slowly descending to the ground: she begins all silly and exciting, bouncing at the corners of the ceiling, but as the movie unfolds her buoyancy diminishes and she comes close to touching the ground. Yet her lightness remains."

Take THAT, paper bag!

Thanks for drawing that connection, js. Wow.

Indeed.

Hmmm . . I kinda want to see this now. Reccomend it?

If you like Woody Allen's domestic comic tragedies (like Hannah or Interiors or Husbands and Wives), yes.

Otherwise, probably not.

Her performance didn't stick with me when I first saw the movie way back when, but your writeup will probably compel me to revisit.

Post a Comment