I am not much of a contrarian by nature. Truly. But given my spoilerish track record on some of the most beloved Supporting Actress performances (exhibit 1, 2), I'm not sure y'all will believe me. As I compose these profiles, I try to tune into my clearest instincts, to not endeavor to sway or convince anyone else but to convey what I honestly think I think about this or that performance. And occasionally that means I end up going against the grain of conventional wisdom about an especially revered performance by a particularly beloved performer, which is precisely what happened this week with...

I am not much of a contrarian by nature. Truly. But given my spoilerish track record on some of the most beloved Supporting Actress performances (exhibit 1, 2), I'm not sure y'all will believe me. As I compose these profiles, I try to tune into my clearest instincts, to not endeavor to sway or convince anyone else but to convey what I honestly think I think about this or that performance. And occasionally that means I end up going against the grain of conventional wisdom about an especially revered performance by a particularly beloved performer, which is precisely what happened this week with...

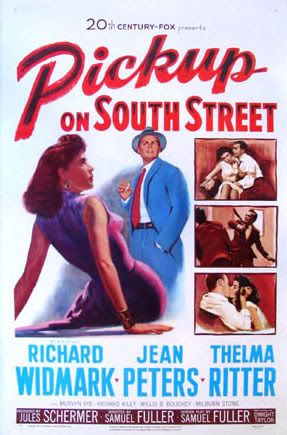

...Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street (1953)

approximately 15 minutes and 43 seconds

6 scenes

roughly 20% of film's total running time

Although she makes her living "selling secrets" in Cold War America, Ritter's Moe balks when called a "stool pigeon," emphasizing her status an enterprising entrepreneur, finding her own way toward success within American capitalism.

Although she makes her living "selling secrets" in Cold War America, Ritter's Moe balks when called a "stool pigeon," emphasizing her status an enterprising entrepreneur, finding her own way toward success within American capitalism. The symbol of Moe's success is her "kitty" -- a wad of bills she's saving toward the purchase of a legitimate funeral plot, a proud gesture in defense of the feared ignominy of her anonymous burial as a pauper in New York City's "Potter's Field."

The symbol of Moe's success is her "kitty" -- a wad of bills she's saving toward the purchase of a legitimate funeral plot, a proud gesture in defense of the feared ignominy of her anonymous burial as a pauper in New York City's "Potter's Field." Ritter's Moe is pivotal to Samuel Fuller's elegantly efficient noir narrative - when Skip (the charismatically opaque Richard Widmark) picks a particular pocket and lands in the sights of both the cops and the communists, Ritter's Moe is the one to whom they turn for the "information" she peddles, and so becomes essential to both the narrative and emotional architecture of this enthralling film.

Ritter's Moe is pivotal to Samuel Fuller's elegantly efficient noir narrative - when Skip (the charismatically opaque Richard Widmark) picks a particular pocket and lands in the sights of both the cops and the communists, Ritter's Moe is the one to whom they turn for the "information" she peddles, and so becomes essential to both the narrative and emotional architecture of this enthralling film. Ritter begins her characterization as the narrative does, with a glib simplicity: Moe's a hustler and she's looking to get on. As the narrative complicates, so does Ritter's work as Moe. When the "muffin" Candy (an appropriately delicious Jean Peters) begins to demonstrate more than a simply mercenary interest in Skip, Ritter's Moe too begins to doubt the economics of her own self-interest. Perhaps the information on Skip's whereabouts is more valuable than she might have originally assessed?

Ritter begins her characterization as the narrative does, with a glib simplicity: Moe's a hustler and she's looking to get on. As the narrative complicates, so does Ritter's work as Moe. When the "muffin" Candy (an appropriately delicious Jean Peters) begins to demonstrate more than a simply mercenary interest in Skip, Ritter's Moe too begins to doubt the economics of her own self-interest. Perhaps the information on Skip's whereabouts is more valuable than she might have originally assessed? Yet, as Moe privately determines that Skips means more to her than money, Ritter allows Moe's zesty bravado deflate just a little. It's as though, absent the thrill of the dollar chase, Moe's not certain what she's living for...

Yet, as Moe privately determines that Skips means more to her than money, Ritter allows Moe's zesty bravado deflate just a little. It's as though, absent the thrill of the dollar chase, Moe's not certain what she's living for... These first two beats -- Moe's (1) the happy hustler who (2) encounters something of an identity crisis -- sets the stage for a final death scene that might just be Thelma Ritter's most glorious five minutes of the actress's deservedly esteemed career.

These first two beats -- Moe's (1) the happy hustler who (2) encounters something of an identity crisis -- sets the stage for a final death scene that might just be Thelma Ritter's most glorious five minutes of the actress's deservedly esteemed career. When Ritter's Moe finds herself not at the shadowy invisible edges of New York's underworld but instead within its glaring spotlight, Thelma Ritter delivers on of the greater death arias I can think of in American cinema. Captured with adoring reverence by director Fuller, Ritter uses a simple monologue to the depth of Moe's sacrifice as she chooses to surrender to death rather than peddle the data of Skip's whereabouts. In this scene, Ritter shows us both "Moe the human calculator" (ever tallying the relative value of the commodities she has to peddle) as well as "Moe the human being" (who operates according to a different, less precise arithmetic). It's a beautiful scene -- warm and moving and memorable -- conveying an unforeseen depth to both the character and the actress.

When Ritter's Moe finds herself not at the shadowy invisible edges of New York's underworld but instead within its glaring spotlight, Thelma Ritter delivers on of the greater death arias I can think of in American cinema. Captured with adoring reverence by director Fuller, Ritter uses a simple monologue to the depth of Moe's sacrifice as she chooses to surrender to death rather than peddle the data of Skip's whereabouts. In this scene, Ritter shows us both "Moe the human calculator" (ever tallying the relative value of the commodities she has to peddle) as well as "Moe the human being" (who operates according to a different, less precise arithmetic). It's a beautiful scene -- warm and moving and memorable -- conveying an unforeseen depth to both the character and the actress. And right there is the rub. For the first 2/3 of her performance, Ritter only shows us the mercenary Moe, with only a glimmer (in the coffee shop scene) of the human soul beneath the hustler's patter. Then, in the last 1/3 of the performance, Ritter reveals a whole 'nother Moe -- the patter suddenly textured and nuanced with revelatory depth. And, normally, I love watching the surface peel back to reveal the unanticipated depth. So believe me when I say I was surprised to discover, after re-viewing the performance for timing and screencapping, what I felt to be a disconnected break between the first 2/3 of Ritter's performance and the last scene. It's as though Ritter trouped through the first few scenes drawing from her standard bag of character actor tricks only to discover, much later, that Moe was not merely a type but a richly reasoned characterization. The problem? This is what the audience should see, but the actor might be expected to see more, to lay the foundation for the culminating reveal with a little more sophistication. Indeed, Moe's first scene in the station provides nearly the entire subtextual foundation for the final scene, yet Ritter opts for a superficial patter and banter that emphasizes the Moe's short term motives at the expense of the character's actual motivations. Put another way, it's as though Ritter skimped on the house and then, at the last minute, splurged on the furniture. Admittedly, this is a fine line I'm parsing here, and one that I acknowledge will get me in trouble with impassioned fans of this performance. But, as I mentioned just recently, one must remain true to one's self, especially in matters of faith, politics and actressexuality. So, in sum: love Ritter, love that death scene, but remain ambivalent about the performance.

And right there is the rub. For the first 2/3 of her performance, Ritter only shows us the mercenary Moe, with only a glimmer (in the coffee shop scene) of the human soul beneath the hustler's patter. Then, in the last 1/3 of the performance, Ritter reveals a whole 'nother Moe -- the patter suddenly textured and nuanced with revelatory depth. And, normally, I love watching the surface peel back to reveal the unanticipated depth. So believe me when I say I was surprised to discover, after re-viewing the performance for timing and screencapping, what I felt to be a disconnected break between the first 2/3 of Ritter's performance and the last scene. It's as though Ritter trouped through the first few scenes drawing from her standard bag of character actor tricks only to discover, much later, that Moe was not merely a type but a richly reasoned characterization. The problem? This is what the audience should see, but the actor might be expected to see more, to lay the foundation for the culminating reveal with a little more sophistication. Indeed, Moe's first scene in the station provides nearly the entire subtextual foundation for the final scene, yet Ritter opts for a superficial patter and banter that emphasizes the Moe's short term motives at the expense of the character's actual motivations. Put another way, it's as though Ritter skimped on the house and then, at the last minute, splurged on the furniture. Admittedly, this is a fine line I'm parsing here, and one that I acknowledge will get me in trouble with impassioned fans of this performance. But, as I mentioned just recently, one must remain true to one's self, especially in matters of faith, politics and actressexuality. So, in sum: love Ritter, love that death scene, but remain ambivalent about the performance.

2 comments:

Hm. I wonder. I am a fan of this performance, though admittedly it has been a while since I've seen it. But I think this parsing of Ritter's work is interesting. What you say makes a lot of sense to me. It's also a kind of standard acting technique, isn't it?: don't play the end of the show at the beginning of the show. The technique makes sense when you see the film only once. And I see why this makes the performance feel off on the second viewing: we're looking for something we know is there and we can't see it. The surprise is already spoiled.

This is good food for thought. I am having trouble thinking through it right now...

I'm still trying to figure out how to figure this out...

But I appreciate your introduction of the "don't play the end" idea, because that really helps me to understand that I don't think the disconnect I'm talking about is really about the surprise.

I keep coming back to the fact that I found it hard to "reconcile" the first scene with the last.

Upon repeated viewing (in which I usually view the performance in as its own "text" - separated from it's surrounding context), I found that the last scene was such a specific characterization of this woman Moe. In contrast, I found the first to be much less specific to the character -- more a standard-issue Ritter perf. At the risk of being cruder than I really want to, I think it boils down to this: For me, it's like she's phoning in the first scene and then acting her balls off in the last. And it's reconciling the two component pieces that I struggle with...

Put another way, I hear a lot about the character in the first scene but don't feel Ritter's work helps me to know/feel her. Then that last scene comes and the whole thing seems to tip off balance...

Post a Comment