There are some performances that I find so compelling, yet so confounding, that I must resort to a default strategy or two as a seek to make sense of all that I'm thinking and feeling. I say this, lovely reader, as I prepare to go all academic on your ass. Because, alas, 'twas the only way I could find my way through the fascinating work of...

There are some performances that I find so compelling, yet so confounding, that I must resort to a default strategy or two as a seek to make sense of all that I'm thinking and feeling. I say this, lovely reader, as I prepare to go all academic on your ass. Because, alas, 'twas the only way I could find my way through the fascinating work of...

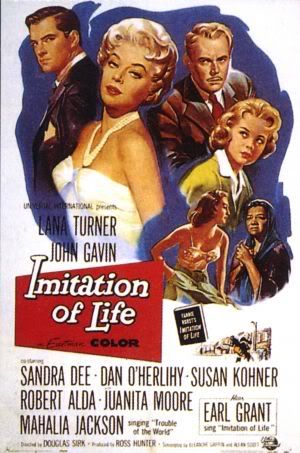

...Susan Kohner in The Imitation of Life (1959)

approximately 21 minutes and 32 seconds

19 scenes

roughly 17% of film's total running time

Kohner's Sarah Jane is, arguably, the most essential character within the narrative of Imitation of Life. Her character's struggle -- as a woman struggling the reconcile the disparity between her aspirations and her obligations -- runs parallel to the struggles experienced by most (if not all) of the other principal characters in the film. However, the particularities of Sarah Jane's conflict -- she's a fair-skinned African American woman who aspires to be white and resents her mother for being (and making her) black -- stands as the most conspicuous iteration of the film's defining "aspiration versus obligation" emotional thematic.

Kohner's Sarah Jane is, arguably, the most essential character within the narrative of Imitation of Life. Her character's struggle -- as a woman struggling the reconcile the disparity between her aspirations and her obligations -- runs parallel to the struggles experienced by most (if not all) of the other principal characters in the film. However, the particularities of Sarah Jane's conflict -- she's a fair-skinned African American woman who aspires to be white and resents her mother for being (and making her) black -- stands as the most conspicuous iteration of the film's defining "aspiration versus obligation" emotional thematic. Indeed, director Douglas Sirk utilizes Sarah Jane's narrative to exploit (and not necessarily in a bad way) midcentury racial anxieties about "passing" (or, more precisely, amalgamation) to both amplify Imitation of Life's conventional mother-daughter dramas and also to transform what are essentially interpersonal/intergenerational tensions into the stuff of socially significant melodrama.

Indeed, director Douglas Sirk utilizes Sarah Jane's narrative to exploit (and not necessarily in a bad way) midcentury racial anxieties about "passing" (or, more precisely, amalgamation) to both amplify Imitation of Life's conventional mother-daughter dramas and also to transform what are essentially interpersonal/intergenerational tensions into the stuff of socially significant melodrama. And where Sarah Jane's narrative compels the dramatic action of the piece, Susan Kohner's performance becomes the film's most compelling spectacle. Is she -- to quote another racial melodrama of the era -- "white enough to pass"? Or is Kohner's "passing performance" a spectacular failure because of the actress's lack of blackness.

And where Sarah Jane's narrative compels the dramatic action of the piece, Susan Kohner's performance becomes the film's most compelling spectacle. Is she -- to quote another racial melodrama of the era -- "white enough to pass"? Or is Kohner's "passing performance" a spectacular failure because of the actress's lack of blackness. Here, Kohner's casting in the role becomes a crucial coordinate of the performance itself. The daughter of Mexican actress Lupita Tovar and a Czech/Jewish film producer, Kohner's ethnic heritage certainly locates her at the outer limits of midcentury U.S. whiteness. (And from a producerly standpoint, casting the ambiguously ethnic but certainly non-African Kohner certainly dodged the "problem" of depicting Sarah Jane having illicit affairs with white men like Tab Hunter.)

Here, Kohner's casting in the role becomes a crucial coordinate of the performance itself. The daughter of Mexican actress Lupita Tovar and a Czech/Jewish film producer, Kohner's ethnic heritage certainly locates her at the outer limits of midcentury U.S. whiteness. (And from a producerly standpoint, casting the ambiguously ethnic but certainly non-African Kohner certainly dodged the "problem" of depicting Sarah Jane having illicit affairs with white men like Tab Hunter.) Yet the narrative of Imitation of Life insists that, through Kohner's Sarah Jane, we dabble in the spectacular "pleasures" of passing performances. The film asks us to believe both that Kohner's Sarah Jane IS black so that we also become anxious when she's perceived as "not" black. Indeed, the film's premise invites us to make the same casual mistake that Lana Turner's Lora makes in the first scene -- to misrecognize Sarah Jane as just another pretty white girl -- and to do so at least twice (once when the character's portrayed by as a child by Karin Dicker, and again about half-way way through when Kohner's introduced). For US viewers in the first, oh, seven or eight decades of the 20th century, such an act of racial misrecognition carried a scandalous taint and director Sirk understands this peculiar (and peculiarly American) obsession with maintaining the legibility of racial distinction. In short, the character of Sarah Jane embodies the reality of racial mixture in the United States and looking at her presents a tacitly scandalous reminder of the fact of black/white "miscegenation."

Yet the narrative of Imitation of Life insists that, through Kohner's Sarah Jane, we dabble in the spectacular "pleasures" of passing performances. The film asks us to believe both that Kohner's Sarah Jane IS black so that we also become anxious when she's perceived as "not" black. Indeed, the film's premise invites us to make the same casual mistake that Lana Turner's Lora makes in the first scene -- to misrecognize Sarah Jane as just another pretty white girl -- and to do so at least twice (once when the character's portrayed by as a child by Karin Dicker, and again about half-way way through when Kohner's introduced). For US viewers in the first, oh, seven or eight decades of the 20th century, such an act of racial misrecognition carried a scandalous taint and director Sirk understands this peculiar (and peculiarly American) obsession with maintaining the legibility of racial distinction. In short, the character of Sarah Jane embodies the reality of racial mixture in the United States and looking at her presents a tacitly scandalous reminder of the fact of black/white "miscegenation." Contemporary "post-racial" viewers, however, are less inclined to project such demands of racial purity upon screen bodies. (Indeed, contemporary audiences seem untroubled when cinematic narratives invite them to "not see" the blackness of such contemporary mixed-race performers as Wentworth Miller, Jennifer Beals or Rashida Jones.) Instead, contemporary audiences appear less concerned with "blood quantum" (the old "one drop of black blood" commonsense still current in 1959) and more invested in racial authenticity. As a cinematic device in contemporary film, blackness is not as much a trope of racial typology as it is a signal of racial identity.

Contemporary "post-racial" viewers, however, are less inclined to project such demands of racial purity upon screen bodies. (Indeed, contemporary audiences seem untroubled when cinematic narratives invite them to "not see" the blackness of such contemporary mixed-race performers as Wentworth Miller, Jennifer Beals or Rashida Jones.) Instead, contemporary audiences appear less concerned with "blood quantum" (the old "one drop of black blood" commonsense still current in 1959) and more invested in racial authenticity. As a cinematic device in contemporary film, blackness is not as much a trope of racial typology as it is a signal of racial identity. Regular StinkyLulu readers, however, by this point or long before, might well ask: what, if anything, does all this racial theory stuff have to do with Susan Kohner's performance? Well, lovely reader, I'd suggest that -- to get to an honest assessment of Kohner's work as an actress in this role -- we have to parse through this history of competing and contradictory cinematic visions of race because they come to collision atop Kohner's performance.

Regular StinkyLulu readers, however, by this point or long before, might well ask: what, if anything, does all this racial theory stuff have to do with Susan Kohner's performance? Well, lovely reader, I'd suggest that -- to get to an honest assessment of Kohner's work as an actress in this role -- we have to parse through this history of competing and contradictory cinematic visions of race because they come to collision atop Kohner's performance. See, for years, I've been hearing Kohner's performance mocked by smart cinemaphiles for all the ways it fails at being black enough. In this view, Kohner's own non-blackness becomes only the first of an accumulation of Kohner's failures in the role. (She doesn't look/sound/feel black at all, or like her mother at all, plus she's annoying and she can't dance.) It's nearly impossible to argue in support of Kohner's performance within such a framework, for Kohner's performance reveals nearly nothing about the historical phenomenon of "passing" in African American history and experience.

See, for years, I've been hearing Kohner's performance mocked by smart cinemaphiles for all the ways it fails at being black enough. In this view, Kohner's own non-blackness becomes only the first of an accumulation of Kohner's failures in the role. (She doesn't look/sound/feel black at all, or like her mother at all, plus she's annoying and she can't dance.) It's nearly impossible to argue in support of Kohner's performance within such a framework, for Kohner's performance reveals nearly nothing about the historical phenomenon of "passing" in African American history and experience. That said, I would submit that Susan Kohner is not really playing a black character in this film but is instead portraying a cinematic concoction devised to complicate assumptions of essential racial difference as it also idealizes notions of human similiarity.

That said, I would submit that Susan Kohner is not really playing a black character in this film but is instead portraying a cinematic concoction devised to complicate assumptions of essential racial difference as it also idealizes notions of human similiarity. Indeed, if we do what is nearly impossible and put the "racial conceit" of Imitation of Life aside for just a moment, we can see that Susan Kohner's accomplishment in the role of Sarah Jane comes from how vividly she expresses the emotional complexities of denying one's familial bonds, responsibilities and histories in the single-minded pursuit of cultural privilege. Considered through such a non-racial lens, Susan Kohner delivers a pungent portrait of a teenager who wants to freed from the shackles of her family's history so that she might be exactly and only who she wants to be.

Indeed, if we do what is nearly impossible and put the "racial conceit" of Imitation of Life aside for just a moment, we can see that Susan Kohner's accomplishment in the role of Sarah Jane comes from how vividly she expresses the emotional complexities of denying one's familial bonds, responsibilities and histories in the single-minded pursuit of cultural privilege. Considered through such a non-racial lens, Susan Kohner delivers a pungent portrait of a teenager who wants to freed from the shackles of her family's history so that she might be exactly and only who she wants to be. The selfishness of Kohner's Sarah Jane stands in dynamic tension with the selflessness of Moore's Annie. The stark contrast fortifies an archetypal mother-daughter conflict, one that both actresses understand and that the film chooses to root in a transcendant vision of mother love.

The selfishness of Kohner's Sarah Jane stands in dynamic tension with the selflessness of Moore's Annie. The stark contrast fortifies an archetypal mother-daughter conflict, one that both actresses understand and that the film chooses to root in a transcendant vision of mother love. Kohner's Sarah Jane spends most of the film denying and defying her mother, doing and saying awful things to the saintly Annie. Yet it's in the moments when Kohner's Sarah Jane recognizes her mother's pain and sacrifice that her characterization really comes alive. Moore's Annie does the hard work of building the emotional foundation of this relationship, but it's Kohner's Sarah Jane who nails the emotional force of the pair's collaboration. For it's Kohner who lets us know that Sarah Jane understands how deeply she's hurting her mother and yet she goes ahead and hurts her anyway.

Kohner's Sarah Jane spends most of the film denying and defying her mother, doing and saying awful things to the saintly Annie. Yet it's in the moments when Kohner's Sarah Jane recognizes her mother's pain and sacrifice that her characterization really comes alive. Moore's Annie does the hard work of building the emotional foundation of this relationship, but it's Kohner's Sarah Jane who nails the emotional force of the pair's collaboration. For it's Kohner who lets us know that Sarah Jane understands how deeply she's hurting her mother and yet she goes ahead and hurts her anyway. I'd be inclined to endorse Kohner's nomination solely for the moment her Sarah Jane flinches when Moore's Annie calls her "Miss Linda." It's a killer moment, showing that Kohner understands the emotional dimensions of the relationship (even if/as she "fails" to amplify the cultural dimensions of the narrative). And it's a moment in which Imitation of Life's lush style, story and actressing converge into something marvelous.

I'd be inclined to endorse Kohner's nomination solely for the moment her Sarah Jane flinches when Moore's Annie calls her "Miss Linda." It's a killer moment, showing that Kohner understands the emotional dimensions of the relationship (even if/as she "fails" to amplify the cultural dimensions of the narrative). And it's a moment in which Imitation of Life's lush style, story and actressing converge into something marvelous. More than most nominated performances, Susan Kohner's performance as Sarah Jane challenges our assumptions, reminding us of the remoteness of the recent past. And whatever social/cultural/racial lenses you happen to wearing as you view this literally extraordinary bit of actressing, be certain to note how thoroughly Susan Kohner nails the emotional infrastructure of this devious daughter's relationship to her doting mother.

More than most nominated performances, Susan Kohner's performance as Sarah Jane challenges our assumptions, reminding us of the remoteness of the recent past. And whatever social/cultural/racial lenses you happen to wearing as you view this literally extraordinary bit of actressing, be certain to note how thoroughly Susan Kohner nails the emotional infrastructure of this devious daughter's relationship to her doting mother. Susan Kohner's may not be a perfect performance; it may not be a complete performance. But Susan Kohner's performance stands as a formidable accomplishment within one of the most complex roles in midcentury cinema.

Susan Kohner's may not be a perfect performance; it may not be a complete performance. But Susan Kohner's performance stands as a formidable accomplishment within one of the most complex roles in midcentury cinema.

10 comments:

I found it a definitely interesting performance - but looking at it from a purely analytical viewpoint (without looking through the lens of historical and societal ideas of 'blackness') i'd say her performance has moments of genius but also some awe-inspiringly bad performance choices (most of which come near the end). Sandra Dee still gives my favorite supporting performance in the film (which, on the whole, I didn't like, but am beginning to appreciate more after reading more about it).

according to imdb margaret o'brien was originally considered for sarah jane - imagine the spectacular lack of blackness she would've brought to the role

i LOVE that story.

thanks for making me giggle, par.

and, slayton, I totally hear you. when she's good, she's very very good; when she's bad, she's embarrassing.

Her "crawdads for me masser" moment still makes me giggle... in a good way. Her crying scene with her mom at the end and her dancing at the club make me giggle... in a not good way.

Slayton, why should she be judged by her dancing?

Sarah Jane was not a ballerina, nor a professional dancer/stripper :) she was a teenager trying to pose as a mature woman, too young for this cabaret/club thing.

I thing it's more believable for her to be a bit more clumsy rather than Liza Minnelli style.

[editing the previous message]:

it's "for her dancing", not by...

and

"I think it's", not thing.

:D

amigo,

we have just finished a Sirk series here in KC ;at the downtown library of all places. of course the very last film was IOL.. post filmic conversation included my observation that Susan K is the least compelling entity in the movie. she is so johnny one note. so institutionally and perfervidly hyterical and that jawline that goes awry if she is not filmed just right. her father was Lana T's agent and Douglas Sirk's agent as well. this may well explain more than anything else her casting in the film.

i could not grasp or comprehend or apprehend your anatomizatiion of blackness--genuine or feigned. it seems to me that you are simply indulging in the narcissism of minor differences. "passing" is a much less traumatic affair than white folks like to imagine.

Fannie Hurst the source of all this nonsense never could really enunciate the truth of things,even as she lived and trusted and depended on her paid companion, chauffeur and confidante, Zora Neale Hurston. their correspondence is illuminating. Hurst was a "sobsister" while Hurston just got on with it. no self pity at all. as they say down in P'cola,"fluff your hair and keep on walking. don't let anyone steal your joy!"

there is so much more to

discuss about this film. it is fabulous entertainment. why though is Ross Hunter completely invisible in the discussion? always! everywhere! he is completely ignored. his presence and thumbprint and creative genius is as apparent and important and necessary to the heartbeat of this film as Sirk's.

thanks so much for this website. i found it quite by accident. what a sweet surprise.

j

I know the post is over a year old but every time someone mentions Lana Turner, it's Susan Kohner that comes to my mind and it's because of this movie. This is a richly detailed film poised at the very end of "Golden Age Hollywood". Both Juantia Moore and Susan Kohner were nominated for Best Supporting Actress. (This isn't a banter about who was better) I just think they both stole the show from Lana Turner. I think the casting was fine, I don't have a problem with Kohner's appearance. The setting was a time (as to some it still remains) that if a person has even a minute part of a black heritage it could create more than the melodrama this film has been touted as being. It would be a complex role even today as I reflect on Jennifer Beals in "The L Word" cast in a very similar way. I think it serves to remind the viewer of how fine the line has been drawn in parts of American culture regarding race or ethnicity.

In my family, my own Native American roots were obscured until after the death of my father. Who could be more American except for white Americans? That was answered with ethnic anonymity on my family.

If it were easier and more essential in "passing" for white meant advancement, ethnic origins could be swept under the rug and this is still true today.

So, the film speaks to me in lots of ways. It's not just a Black/White issue, it's any ethic group vs. White people.

It's a long and sometimes tedious movie but I occasionally return to it but as issues goes, something I'd call a "sleeper". Thanks for the page. Part of my interest is that I like looking at Susan Kohner, that part is simple.

Has anyone of you ever seen the original movie 1934??

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0025301/?ref_=ttmd_md_nm

White widow Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) and her daughter Jessie (Juanita Quigley as a toddler, Marilyn Knowlden as an eight-year-old) take in black housekeeper Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers) and her daughter, light-complexioned Peola (Fredi Washington) exchanging room and board for work, even though Bea is struggling to make ends meet herself. Delilah and Peola quickly become like family to Jessie and Bea. They particularly enjoy Delilah's pancakes, made from a special family recipe. When Bea is unable to make a living selling pancake syrup (as her husband had done), she comes up with the idea to open a pancake restaurant (using Delilah's recipe and labor) on the boardwalk, which proves to be very profitable. Later, at the suggestion of Elmer Smith (Ned Sparks), she sets up an even more successful pancake flour corporation, marketing Delilah as an Aunt Jemima-like figure. As a result, Bea becomes a wealthy business woman, but all is not found to be well as the story advances fifteen years. Eighteen-year-old Jessie (Rochelle Hudson) falls in love with her mother's boyfriend, Steven Archer (Warren William), who is unaware at first of her affections. Meanwhile, Peola (Fredi Washington), ashamed of her African-American heritage, attempts to pass as white, breaking Delilah's heart. Peola eventually runs away from home. While she is away, Delilah falls ill and dies. Delilah wished for a large, grand funeral, which Bea provides for her, complete with a marching band and a horse-drawn hearse. Just before the processional begins, a remorseful, crying Peola appears, begging her mother to forgive her. The film ends with Bea breaking her engagement with Steven because of the situation with Jessie.

Has anyone of you ever seen the original - 1934

( it's good to see them both)

White widow Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) and her daughter Jessie (Juanita Quigley as a toddler, Marilyn Knowlden as an eight-year-old) take in black housekeeper Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers) and her daughter, light-complexioned Peola (Fredi Washington) exchanging room and board for work, even though Bea is struggling to make ends meet herself. Delilah and Peola quickly become like family to Jessie and Bea. They particularly enjoy Delilah's pancakes, made from a special family recipe. When Bea is unable to make a living selling pancake syrup (as her husband had done), she comes up with the idea to open a pancake restaurant (using Delilah's recipe and labor) on the boardwalk, which proves to be very profitable. Later, at the suggestion of Elmer Smith (Ned Sparks), she sets up an even more successful pancake flour corporation, marketing Delilah as an Aunt Jemima-like figure. As a result, Bea becomes a wealthy business woman, but all is not found to be well as the story advances fifteen years. Eighteen-year-old Jessie (Rochelle Hudson) falls in love with her mother's boyfriend, Steven Archer (Warren William), who is unaware at first of her affections. Meanwhile, Peola (Fredi Washington), ashamed of her African-American heritage, attempts to pass as white, breaking Delilah's heart. Peola eventually runs away from home. While she is away, Delilah falls ill and dies. Delilah wished for a large, grand funeral, which Bea provides for her, complete with a marching band and a horse-drawn hearse. Just before the processional begins, a remorseful, crying Peola appears, begging her mother to forgive her. The film ends with Bea breaking her engagement with Steven because of the situation with Jessie.

Post a Comment