I'm reminded this week that there's a certain stripe of legendary midcentury American actors who, quite simply, leave me nonplussed. I find them electrifying, fascinating, and occasionally quite moving yet, at the same time, I find them utterly confounding. To put it simply, I can always remember their performance but I can never remember their character. They're the kind of actors, often steeped in some version of "The Method," who forego chameleonic transformation in favor of vivid behaviorism. You sorta always know it's them and, implicitly, that the character is sorta secondary to the work of being "real" and "in the moment." It's not a persona thing, per se. The spectacle is not the performer herself but "the work" she's doing. The role, the story, the filmmaking is secondary to "the work" of the acting. I'm not sure this makes any sense, but it's my way of searching for an explanation of why I find myself so perplexed by "the work" done by...

I'm reminded this week that there's a certain stripe of legendary midcentury American actors who, quite simply, leave me nonplussed. I find them electrifying, fascinating, and occasionally quite moving yet, at the same time, I find them utterly confounding. To put it simply, I can always remember their performance but I can never remember their character. They're the kind of actors, often steeped in some version of "The Method," who forego chameleonic transformation in favor of vivid behaviorism. You sorta always know it's them and, implicitly, that the character is sorta secondary to the work of being "real" and "in the moment." It's not a persona thing, per se. The spectacle is not the performer herself but "the work" she's doing. The role, the story, the filmmaking is secondary to "the work" of the acting. I'm not sure this makes any sense, but it's my way of searching for an explanation of why I find myself so perplexed by "the work" done by...

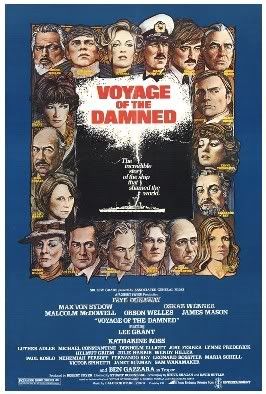

...Lee Grant in Voyage of the Damned (1976)

approximately 12 minutes and 1 second

18 scenes

roughly 8% of film's total running time

Grant's Lili Rosen is a tightly wired woman, apparently accustomed to some degree of privilege, whose existence to no small degree is defined through her relationships with her very pretty daughter, Anna (Lynne Frederick, in an unfortunately bland performance)...

Grant's Lili Rosen is a tightly wired woman, apparently accustomed to some degree of privilege, whose existence to no small degree is defined through her relationships with her very pretty daughter, Anna (Lynne Frederick, in an unfortunately bland performance)... ...as well as her relationship to her husband, Carl (Sam Wanamaker, in a curiously obtuse performance).

...as well as her relationship to her husband, Carl (Sam Wanamaker, in a curiously obtuse performance). Lil's husband has apparently borne the ignominy of Nazi persecution with a brittle, stubborn forbearance that manifests in a barely contained rage, a fury that blasts forth with little warning and occasionally catches Grant's Lili in the cross-fire. Nonetheless, Grant's Lili suffers her husband's thoughtless brutalities with instinctive empathy and attentive concern.

Lil's husband has apparently borne the ignominy of Nazi persecution with a brittle, stubborn forbearance that manifests in a barely contained rage, a fury that blasts forth with little warning and occasionally catches Grant's Lili in the cross-fire. Nonetheless, Grant's Lili suffers her husband's thoughtless brutalities with instinctive empathy and attentive concern. As her husband begins what seems to be an inexorable decline into paranoid psychosis, Grant's Lili -- skittish, tense and afraid already -- watches with a private desperation. Yet, at the same time, ostensibly for the sake of her young adult daughter, Grant's Lili tries to affirm the hope in her family's journey to the new world. In spite of her ministrations, however, Carl continues to slowly succumb to the overwhelming fear created by the situation.

As her husband begins what seems to be an inexorable decline into paranoid psychosis, Grant's Lili -- skittish, tense and afraid already -- watches with a private desperation. Yet, at the same time, ostensibly for the sake of her young adult daughter, Grant's Lili tries to affirm the hope in her family's journey to the new world. In spite of her ministrations, however, Carl continues to slowly succumb to the overwhelming fear created by the situation. In an effort to protect her daughter from seeing what's becoming of her father, Grant's Lili makes what turns out to be a fateful move: she commands her daughter to go up to the deck and make friends with some young people (which Anna does, meeting a cute deckhand with whom she begins an ill-fated romance).

In an effort to protect her daughter from seeing what's becoming of her father, Grant's Lili makes what turns out to be a fateful move: she commands her daughter to go up to the deck and make friends with some young people (which Anna does, meeting a cute deckhand with whom she begins an ill-fated romance). Though neither Grant nor the film really make a point of it, the tragedies that chart the rest of Lili Rosen's character arc -- and, notably, the plot itself -- are scored in this scene, where Lili desperately seeks to give her husband and her daughter the confidence, the hope, to survive the ordeal.

Though neither Grant nor the film really make a point of it, the tragedies that chart the rest of Lili Rosen's character arc -- and, notably, the plot itself -- are scored in this scene, where Lili desperately seeks to give her husband and her daughter the confidence, the hope, to survive the ordeal. Lili's character arc also scores the film's own tragic turns. First, the character is at the center of the film's emotional storm when, having been refused entry to Havana, the ship starts pulling back to sea. The sound of the ship's horns causes Carl -- the husband of Grant's Lili -- to experience a psychotic episode where, with straight razor in hand, he flails across the upper deck, slicing his arms bloody until he dives off the ship's deck. Cuban authorities take Carl away -- Lili doesn't know whether to hospital or to his death -- and Grant's Lili is left unmoored by one of her key coordinates of existence. The film's next tragic shift happens when, having been refused entry to the U.S., the St. Louis charts its return course to Hamburg. The terror of a return to Germany inspires Anna and her sailor boyfriend to make a suicide pact and, with Anna's death, Grant's Lili loses her sole other purpose for living.

Lili's character arc also scores the film's own tragic turns. First, the character is at the center of the film's emotional storm when, having been refused entry to Havana, the ship starts pulling back to sea. The sound of the ship's horns causes Carl -- the husband of Grant's Lili -- to experience a psychotic episode where, with straight razor in hand, he flails across the upper deck, slicing his arms bloody until he dives off the ship's deck. Cuban authorities take Carl away -- Lili doesn't know whether to hospital or to his death -- and Grant's Lili is left unmoored by one of her key coordinates of existence. The film's next tragic shift happens when, having been refused entry to the U.S., the St. Louis charts its return course to Hamburg. The terror of a return to Germany inspires Anna and her sailor boyfriend to make a suicide pact and, with Anna's death, Grant's Lili loses her sole other purpose for living. Grant's Lili reacts to the loss of Carl and the death of Anna with a primitive, traditional grief instinct and begins to cut her hair as a gesture of atonement for her failings in allowing her daughter to die. Her private ritual of self-scarification is interrupted by an elegant fellow passenger (Faye Dunaway in a simplistic but effective performance as a proud woman attempting to maintain her strength in the face of successive humiliations).

Grant's Lili reacts to the loss of Carl and the death of Anna with a primitive, traditional grief instinct and begins to cut her hair as a gesture of atonement for her failings in allowing her daughter to die. Her private ritual of self-scarification is interrupted by an elegant fellow passenger (Faye Dunaway in a simplistic but effective performance as a proud woman attempting to maintain her strength in the face of successive humiliations). Grant's Lili asserts the righteousness of her devastating grief, fighting against any attempts to stop her with a feral desperation, until she is stopped by the news that her husband has indeed survived his injuries. In this moment, Grant's Lili discovers a faint, grim, weary willingness to live again and surrenders somewhat to the support being offered her by a fellow survivor.

Grant's Lili asserts the righteousness of her devastating grief, fighting against any attempts to stop her with a feral desperation, until she is stopped by the news that her husband has indeed survived his injuries. In this moment, Grant's Lili discovers a faint, grim, weary willingness to live again and surrenders somewhat to the support being offered her by a fellow survivor. Grant's performance in the role of Lili Rosen is vivid. In every moment, Grant's Lili is alive with electric emotion and a palpable psychology. You can see Lili's mind working in flashes across Grant's face. Yet, as powerfully as Grant tunes me into what the character's thinking and feeling, I remain uncertain about who Lili Rosen is. Grant is so "in the moment" that my connection to Lili Rosen's backstory is tenuous. For example, when Carl inadvertently backhands Lili, I don't know if Grant's complicated reaction of fear, sadness and embarassment is something Lili's long accustomed to doing (as a cover for her bullying, possibly abusive husband) or whether it's a spontaneous coping mechanism (as a suggestion that Lili's as surprised as her daughter by Carl's sudden transformation). Likewise, I wonder if Grant's assiduously regal bearing doesn't get in the way of conveying the full force of Lili's desperation. (Indeed, I wonder if Lili and Carl are supposed to be a little nouveau riche, but one generation removed from the shtetl, and if that's not supposed to be part of what amplifies their crisis in the collapse of the new social order, and possibly explains the vague disdain with which the professor and his wife regard them.) Moreover, I'm a total sucker for a hair-shearing scene but, here, I found the action "stunty." I had no idea, from Grant's performance in the role, as to whether such an elemental gesture was in or out of character for Lili Rosen. In short, Lee Grant provides a vivid portrait of what the character is thinking and feeling in each moment even as she delivers only the most rudimentary sketch of who the character is.

Grant's performance in the role of Lili Rosen is vivid. In every moment, Grant's Lili is alive with electric emotion and a palpable psychology. You can see Lili's mind working in flashes across Grant's face. Yet, as powerfully as Grant tunes me into what the character's thinking and feeling, I remain uncertain about who Lili Rosen is. Grant is so "in the moment" that my connection to Lili Rosen's backstory is tenuous. For example, when Carl inadvertently backhands Lili, I don't know if Grant's complicated reaction of fear, sadness and embarassment is something Lili's long accustomed to doing (as a cover for her bullying, possibly abusive husband) or whether it's a spontaneous coping mechanism (as a suggestion that Lili's as surprised as her daughter by Carl's sudden transformation). Likewise, I wonder if Grant's assiduously regal bearing doesn't get in the way of conveying the full force of Lili's desperation. (Indeed, I wonder if Lili and Carl are supposed to be a little nouveau riche, but one generation removed from the shtetl, and if that's not supposed to be part of what amplifies their crisis in the collapse of the new social order, and possibly explains the vague disdain with which the professor and his wife regard them.) Moreover, I'm a total sucker for a hair-shearing scene but, here, I found the action "stunty." I had no idea, from Grant's performance in the role, as to whether such an elemental gesture was in or out of character for Lili Rosen. In short, Lee Grant provides a vivid portrait of what the character is thinking and feeling in each moment even as she delivers only the most rudimentary sketch of who the character is. I admire this performance with the same ambivalence I discover in most Lee Grant performances from the 1970s. In the character of Lili Rosen, I find myself searching Lee Grant's performance for a clue to who Lili Rosen was before this crisis, a search that seems frustrated by Grant's performance itself. Indeed, I find that Lee Grant's work illuminates the character's psychology with an often electrifying vivacity. Yet at the same time, I often feel I'm watching the actress perform the emotion instead of the character. It's too bad, too, because the stuff Grant does do is great. I only wish she had got around to doing the rest...

I admire this performance with the same ambivalence I discover in most Lee Grant performances from the 1970s. In the character of Lili Rosen, I find myself searching Lee Grant's performance for a clue to who Lili Rosen was before this crisis, a search that seems frustrated by Grant's performance itself. Indeed, I find that Lee Grant's work illuminates the character's psychology with an often electrifying vivacity. Yet at the same time, I often feel I'm watching the actress perform the emotion instead of the character. It's too bad, too, because the stuff Grant does do is great. I only wish she had got around to doing the rest...

27 comments:

I'll give more details at the end of the month, but I really really didn't like this performance. Yet, to be honest, there isn't a character to work with (for any of the actors as a matter of fact - I thought the screenplay was quite bad, trying to hard and failing big.)

Lots of stars, but this is no Robert Altman movie...

I was a bit surprised by your positive remark on Faye Dunaway. I thought she was the worst of the cast (well, she & Grant's husband). Her acting in her scene with Grant was all over the place.

I did love Oskar Werner though.

...there's a certain stripe of legendary midcentury American actors who, quite simply, leave me nonplussed. I find them electrifying, fascinating, and occasionally quite moving yet, at the same time, I find them utterly confounding.... They're the kind of actors, often steeped in some version of "The Method," who forego chameleonic transformation in favor of vivid behaviorism.

I'm genuinely curious - besides Lee Grant, who else would you put into this category?

Kim Stanley? Arthur Kennedy?

I think this discussion of acting and how it works is very interesting. One of my favorite of the things you do with this blog is interrogate your own responses to performances and films and try to figure out what elicits the response. I love it.

*

This film was weirdly shot, if I remember correctly. It's an odd little movie. It's been years since I saw it, but the only thing I really remember is that hair-cutting scene.

Thanks, Aaron, I think you've put your finger on my interpretive POV in this project.

As for your question, Buck:

I'm still working on that list but I'm pretty sure it includes most of the pivotal Actor's Studio folks for the 1960s and into the early 1970s (Grant, Gazzara, Pacino, Estelle Parsons).

The best clarifying example I can think of:

Compare Pacino, Hoffman and De Niro in the 1970s. Pacino's always amazing but always sorta Pacino, while the other two do a little more "disappearing into" their roles. They're all working from the core premises of the American Method, but Pacino's flavor is slightly different.

Funny, for me Hoffman and De Niro have long-since ceased to be interesting performers. But I am still rather consistently interested in Pacino's work.

I totally see what you're saying when I think of Lee Grant (and Pacino too, really) but Pacino is still an actor I like watching, while both De Niro and Hoffman always feel to me nowadays as though they are working too hard--acting too much. (Maybe this has happened with Pacino, too, and I am just not noticing it...)

I'm not sure how I'd square this comparison with Hoffman and DeNiro since, say, the mid 1980s.

But in the 1970s (at least up until 1980's Scarface), I find the comparison useful.

(That said, in recent years, I have found Pacino nearly unwatchable, except in that movie where he plays satan.)

good blog entry I forgot how much I enjoyed "parts" of this movie....

just ordered it from Ebay

Watching Taxi Driver again, I couldn't help but ask: WHAT happened to De Niro?? He used to be magic! :(

Random:

Allegedly, Lee Grant is great in Detective Story (1951) with her winning at Cannes and all of that.

Though, I would never want 1951 to win the poll for the smackdown, as I wouldn't wanna pay 1000$ to get a copy of The Blue Veil. :P

seems 2 me that both gloria grahame and lee grant could have very easily traded parts over the yrs...

Gloria Grahame? I just can't get over her outrageous Oscar win. :(

but let's not get people started on 1952! :)

Gloria Grahame doesn't seem Methody.

Please please please, for the love of God, tell me that Ellen Burstyn belongs in this clique of people who are good actors but also sort of rub your nose in "The Work." Because what you say at the top of this post is a perfect account of how I almost always feel about Burstyn, both when she's "good" and when she "isn't." And, most frequently, when you can't even tell, because of the "Work" thing.

You might feel differently, but I'm hoping you don't. I have a hankering for some corroboration.

in regards 2 ellen burstyn...she was in a documentary once where it showed her being lead thru a battery of psychological experiments w/lee strasberg...it was supposed 2 be helping her w/her acting 4 an upcoming role...i found it 2 be BOGUS!!! there was no need 4 all of that...the psych stuff needed 2 be done w/ an analyst, not a drama coach...sanford meisner said it best...ALL THAT ACTING REQUIRES IS 2 BE AS REAL AS POSSIBLE IN AN IMAGINARY SCENARIO...case closed...

Two things I found hysterically funny in "Voyage of the Damned"

1) The '70s hair styles and costumes in a movie set in 1939

2) The hair cutting scene, in which Dunaway takes the scissors from Lee Grant and snips away at Grant's hair, snarling, "Look at yourself!" It's right out of "Mommie Dearest"--but five years earlier! Strangely, hilariously prophetic!

The '70s hair styles and costumes in a movie set in 1939

The 70s were not very helpful to period pics in this way...

The hair cutting scene, in which Dunaway takes the scissors from Lee Grant and snips away at Grant's hair, snarling, "Look at yourself!" It's right out of "Mommie Dearest"--but five years earlier! Strangely, hilariously prophetic!

I have to say the monocle scene also provided a glimpse into just how fabulously ridiculous Faye could be...

Oh - NICK -

I tend to fall in for Burstyn more easily, but I would suspect that, yes, it's Burstyn too.

I keep thinking of how weirdly off she was in Ya Ya Sisterhood as my best example of Burstyn doing what I'm talking about.

Alex: Grant is good in "Detective Story", but a little ham-handed in the role.

I really like Lee Grant, but I have to confess she often fails to flesh out her performances fully, relying on surface emotion and lots of background emoting. She stood out in "Voyage of the Damned" but only because 99% of the cast was so bland. James Mason was sleepwalking through his cameo and poor Orson couldn't go more than 2 words without having to take a deep breath.

Katharine Ross winning the Golden Globe for this is just hilarious :)

Her second scene might have been effective here and there, but the first one... ooooh baaad. I actually thought it might be her only scene in the entire movie, I didn't expect the character to come back.

One of the few GG winners snubbed by Oscar. It was a wise snub.

I actually liked Ross in this quite a bit.

Stinky: Good call--why on earth was Faye wearing a monocle and knee-high boots in that costume-ball scene? Had she decided to come as a Nazi? (I hope not.)

This is such a great post, and an excellent question--when does an actor's process become what you're seeing, rather than an actual performance?

In this particular case, though, I hesitate to put the finger on Grant, at least not entirely, because the screenplay was such a mess. She was dealing with writing that relied very, very heavily on our knowledge of what lay ahead for these people and Europe, and not on creating individuals. It's similar to the problem I was trying to describe when I wrote up a French TV film about the Nazi persecution of homosexuals. At least Grant creates a woman who is fascinating to watch, even if she doesn't live for us as an actual human being.

I prefer Stanley Kramer's similarly themed Ship of Fools to this movie, despite Kramer's usual dull directing. That movie had the same anachronistic costume/hair problem though, even more so than Voyage of the Damned.

I think Nick's example of Ellen Burstyn is a good one. Debra Winger would be another one for me.

Your idea of certain actors playing a role as a series of emotional cues rather than as an actual personality brings to mind Ellen Burstyn in "W.", which I just saw last night. Bad movie, bad performance.

matt: Dunaway's monocle and boot costume is indeed a costume, as they're going to a costume dance. But it's also a callback to the late 1920s-early 1930s Weimar fashion, when women wore monocles and boots deliberately. Anita Berber is the best example, but Ginger Rogers also wears a monocle in "42nd Street", an affectation the character claims to have picked up while in Europe.

Faye Dunaway was great in this and absolutely gorgeous as always

Post a Comment