Rarely, lovely reader, have I so struggled in resolving my feelings about a performance as I did while developing this week's profile. It's a legendary performance by a legendary performer, one I'm still struggling to parse out for myself. Of course, I'm talking about...

Rarely, lovely reader, have I so struggled in resolving my feelings about a performance as I did while developing this week's profile. It's a legendary performance by a legendary performer, one I'm still struggling to parse out for myself. Of course, I'm talking about...

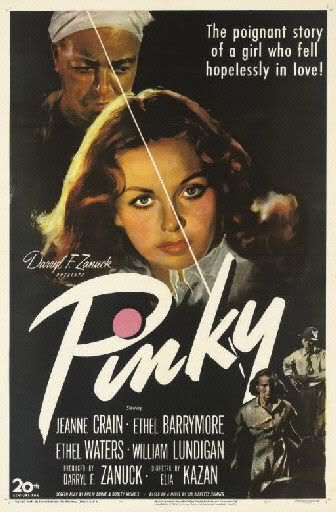

...Ethel Waters in Pinky (1949)

approximately 29 minutes and 57 seconds

21 scenes

roughly 29% of film's total running time

Pinky, the film's title, refers of course to the nickname given Aunt Dicey's granddaughter, Patricia, a fair-skinned young black woman recently returned from the North where she "passed" for white while pursuing her nursing degree.

Pinky, the film's title, refers of course to the nickname given Aunt Dicey's granddaughter, Patricia, a fair-skinned young black woman recently returned from the North where she "passed" for white while pursuing her nursing degree. Waters's Aunt Dicey, of course, disapproves of Pinky's "passing" deception, affirming the core moral of this tale ("you must be decent to others and 'true' to yourself, no matter the consequences").

Waters's Aunt Dicey, of course, disapproves of Pinky's "passing" deception, affirming the core moral of this tale ("you must be decent to others and 'true' to yourself, no matter the consequences"). Waters is formidable in the humble role of Aunt Dicey, especially in the films first several scenes when she's laying down the exposition while also communicating how a humble black woman in the Jim Crow South might maintain her self-respect in the face of daily indignities (a faith in God, a commitment to doing the right thing, and a clear understanding of one's place). Yet Waters's Aunt Dicey is also one of the films most prominent defenders of the existing, racially segregated social order. In many ways, Aunt Dicey is the character who feels the film's central conflict most profoundly: Aunt Dicey's compelled to support her granddaughter as Pinky attempts to honor Miss Em's dying wishes; at the same time, Aunt Dicey's mortally terrified of so violating the social codes of the day.

Waters is formidable in the humble role of Aunt Dicey, especially in the films first several scenes when she's laying down the exposition while also communicating how a humble black woman in the Jim Crow South might maintain her self-respect in the face of daily indignities (a faith in God, a commitment to doing the right thing, and a clear understanding of one's place). Yet Waters's Aunt Dicey is also one of the films most prominent defenders of the existing, racially segregated social order. In many ways, Aunt Dicey is the character who feels the film's central conflict most profoundly: Aunt Dicey's compelled to support her granddaughter as Pinky attempts to honor Miss Em's dying wishes; at the same time, Aunt Dicey's mortally terrified of so violating the social codes of the day. Aunt Dicey's dilemma is a potentially powerful one, and Waters seems entirely capable of delivering a knockout dramatic performance, yet Elia Kazan's film finds itself more invested in what becomes the core relationship between Pinky and Miss Em (a narrative that is more about accessing the privileges of whiteness than about dealing with the shifting meanings of blackness). So, without much attention from the script or the camera (or, most notably, her own costars), Waters is left pretty much on her own and, perhaps as a result, her performance is marked by curious moments of stylistic discordance.

Aunt Dicey's dilemma is a potentially powerful one, and Waters seems entirely capable of delivering a knockout dramatic performance, yet Elia Kazan's film finds itself more invested in what becomes the core relationship between Pinky and Miss Em (a narrative that is more about accessing the privileges of whiteness than about dealing with the shifting meanings of blackness). So, without much attention from the script or the camera (or, most notably, her own costars), Waters is left pretty much on her own and, perhaps as a result, her performance is marked by curious moments of stylistic discordance. An organic naturalism amplifies some scenes (as when Waters conveys the potency of Aunt Dicey's grief at Miss Em's imminent passing) while stock posturing diminishes others (as when Waters's face freezes in a broad but hollow grin as she ventures to check on Miss Em, or in a mask of uncertain anxiety as the huckster Jake waxes ominous).

An organic naturalism amplifies some scenes (as when Waters conveys the potency of Aunt Dicey's grief at Miss Em's imminent passing) while stock posturing diminishes others (as when Waters's face freezes in a broad but hollow grin as she ventures to check on Miss Em, or in a mask of uncertain anxiety as the huckster Jake waxes ominous). Waters is good in the role, sometimes great. But the film remains uninterested in Aunt Dicey, except as its symbol of everything good in a basically awful social system.

Waters is good in the role, sometimes great. But the film remains uninterested in Aunt Dicey, except as its symbol of everything good in a basically awful social system. Basically, the film situates Aunt Dicey as someone to be treasured, to be honored, and to be pitied.

Basically, the film situates Aunt Dicey as someone to be treasured, to be honored, and to be pitied. And Waters does what she can to elevate the role beyond its base simplicity, but even a performer as formidable as Waters can only do so much when the film seems to be working against her. The film may be "about" the immoral idiocies of the color line but the film also fails to invest Aunt Dicey's character (and, by extension, Ethel Waters' performance) with the possibility of dynamic personhood. (And it's probably best to not get me started on the ignominy of Aunt Dicey's final scene, an ostensibly "lightly mocking" moment which bears a barely hidden cruelty -- to actress and to character -- that I find utterly shocking.)

And Waters does what she can to elevate the role beyond its base simplicity, but even a performer as formidable as Waters can only do so much when the film seems to be working against her. The film may be "about" the immoral idiocies of the color line but the film also fails to invest Aunt Dicey's character (and, by extension, Ethel Waters' performance) with the possibility of dynamic personhood. (And it's probably best to not get me started on the ignominy of Aunt Dicey's final scene, an ostensibly "lightly mocking" moment which bears a barely hidden cruelty -- to actress and to character -- that I find utterly shocking.) Waters' performance in Pinky presents a frustrating conundrum. Her Aunt Dicey is, by turns, vivid and blurry. Waters presents a completely realized characterization in one moment, a 2nd tier stock performance in the next. It's an erratic performance of a complicated role that seems to have been directed with benign (?) neglect. A worthy nomination for a formidable performer, to be sure, but the performance itself remains a confounding mess that I yet struggle to sort through.

Waters' performance in Pinky presents a frustrating conundrum. Her Aunt Dicey is, by turns, vivid and blurry. Waters presents a completely realized characterization in one moment, a 2nd tier stock performance in the next. It's an erratic performance of a complicated role that seems to have been directed with benign (?) neglect. A worthy nomination for a formidable performer, to be sure, but the performance itself remains a confounding mess that I yet struggle to sort through.

No comments:

Post a Comment