My decision to undertake "Supporting Actress Sundays" as an ongoing multiyear "research" project was informed in no small part by my desire to fill in some of the many gaps in my cinematic knowledge/experience. For all the obscure movies I've seen, sometimes multiple times, there are canonical films I've somehow missed. I figured that a project like Supporting Actress Sundays might broaden my curiosities, expand my appreciations, and force me to screen some of those movies I've been avoiding so assiduously. Over the past couple years, I've been able to tick off one or two items on my "movies I'm secretly avoiding" list but your selection for the month of June finally forces me face to face down one of the most gargantuan, embarassing gaps in my cinematic experience. And so, at long last, I hunker down and take a good look at...

My decision to undertake "Supporting Actress Sundays" as an ongoing multiyear "research" project was informed in no small part by my desire to fill in some of the many gaps in my cinematic knowledge/experience. For all the obscure movies I've seen, sometimes multiple times, there are canonical films I've somehow missed. I figured that a project like Supporting Actress Sundays might broaden my curiosities, expand my appreciations, and force me to screen some of those movies I've been avoiding so assiduously. Over the past couple years, I've been able to tick off one or two items on my "movies I'm secretly avoiding" list but your selection for the month of June finally forces me face to face down one of the most gargantuan, embarassing gaps in my cinematic experience. And so, at long last, I hunker down and take a good look at...

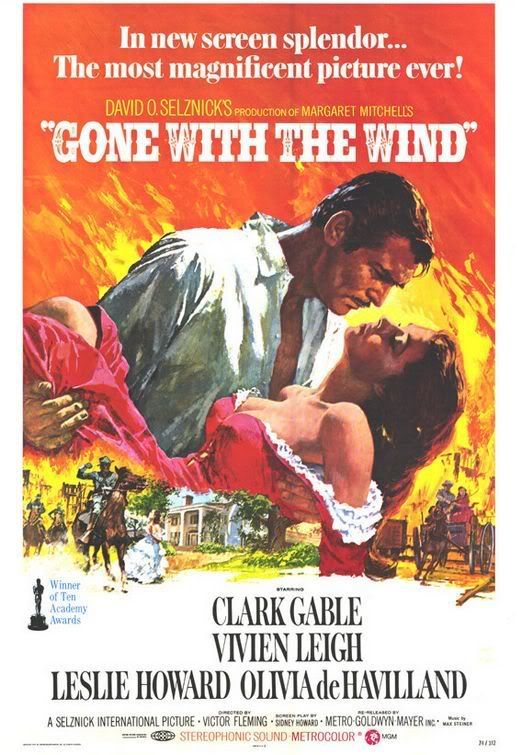

...Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Wind (1939)

approximately 20 minutes and 2 seconds

31 scenes

roughly 9% of film's total running time

The narrative suggests that McDaniel's Mammy arrived to the O'Hara household by marriage, as the maid/possession of the saintly mother of the house Miss Ellen (Barbara O'Neil laying the foundation for her bad mommy nomination the following year). Though still devoted to O'Neil's Miss Ellen, it seems that McDaniel's Mammy has spent much of the last two decades keeping track of the eldest O'Hara daughter, Scarlett (Vivien Leigh in an enduring, iconic performance).

The narrative suggests that McDaniel's Mammy arrived to the O'Hara household by marriage, as the maid/possession of the saintly mother of the house Miss Ellen (Barbara O'Neil laying the foundation for her bad mommy nomination the following year). Though still devoted to O'Neil's Miss Ellen, it seems that McDaniel's Mammy has spent much of the last two decades keeping track of the eldest O'Hara daughter, Scarlett (Vivien Leigh in an enduring, iconic performance). Hattie McDaniel's performance in the role of Mammy -- a devoted domestic who continues to work for her former owners even after emancipation -- is rife with contradictions, both within the film but especially beyond it. Perhaps most notably, McDaniel (herself the daughter of ex-slaves) was the first African American performer to be nominated for an Academy Award and the first to win. This accomplishment did little to broaden professional opportunities for McDaniel or other black performers. It would be ten years before another African American performer would be nominated in a competitive acting category (Ethel Waters's nomination in the same category and in a not unsimilar role in 1949's Pinky) and nearly a quarter century before Sidney Poitier -- the 2nd African American Oscar winner -- was recognized for a not unsimilar role in 1963's Lilies of the Field. Yet, while I remain interested in the historical context and significance of McDaniel's win, I'm also fascinated by McDaniel's performance in this limited and limiting role.

Hattie McDaniel's performance in the role of Mammy -- a devoted domestic who continues to work for her former owners even after emancipation -- is rife with contradictions, both within the film but especially beyond it. Perhaps most notably, McDaniel (herself the daughter of ex-slaves) was the first African American performer to be nominated for an Academy Award and the first to win. This accomplishment did little to broaden professional opportunities for McDaniel or other black performers. It would be ten years before another African American performer would be nominated in a competitive acting category (Ethel Waters's nomination in the same category and in a not unsimilar role in 1949's Pinky) and nearly a quarter century before Sidney Poitier -- the 2nd African American Oscar winner -- was recognized for a not unsimilar role in 1963's Lilies of the Field. Yet, while I remain interested in the historical context and significance of McDaniel's win, I'm also fascinated by McDaniel's performance in this limited and limiting role. The role of Mammy in Gone with the Wind is a familiar one, both to the audiences of 1939 as well as those in the 21st century. She's the big-hearted, big-bodied, big-mouthed, brown-skinned woman, inclined to speaking truths no one else will while also being a reliably devoted servant to the cause of white familial security and harmony.

The role of Mammy in Gone with the Wind is a familiar one, both to the audiences of 1939 as well as those in the 21st century. She's the big-hearted, big-bodied, big-mouthed, brown-skinned woman, inclined to speaking truths no one else will while also being a reliably devoted servant to the cause of white familial security and harmony. Yet, the role of Mammy in Gone with the Wind serves additional purposes as well. McDaniel's Mammy is both comic foil to Leigh's Scarlett as well as, curiously enough, the audience's primary surrogate in keeping track of Scarlett's myriad manipulations. Indeed, Mammy and Rhett are the only two characters who understand Scarlett (though Olivia de Haviland's Melanie is smarter than she looks) and the film offers Mammy as a kind of moral compass for its heroine's actions.

Yet, the role of Mammy in Gone with the Wind serves additional purposes as well. McDaniel's Mammy is both comic foil to Leigh's Scarlett as well as, curiously enough, the audience's primary surrogate in keeping track of Scarlett's myriad manipulations. Indeed, Mammy and Rhett are the only two characters who understand Scarlett (though Olivia de Haviland's Melanie is smarter than she looks) and the film offers Mammy as a kind of moral compass for its heroine's actions. In short, Gone with the Wind utilizes the simplistic character of Mammy in sometimes complex ways and it's in this complexity that McDaniel herself makes much more of this role than might seem possible on first glance.

In short, Gone with the Wind utilizes the simplistic character of Mammy in sometimes complex ways and it's in this complexity that McDaniel herself makes much more of this role than might seem possible on first glance. McDaniel is a gifted comedienne, familiar with the bits and the shticks that made blackness funny in 1930s Hollywood, and she utilizes those skills with acuity as Mammy. McDaniel's Mammy and Gable's Rhett Butler are the only characters in the film capable of making fun of Leigh's Scarlett, and their loving mockery helps to lighten the often overwrought film. McDaniel maneuvers the utterly conventional (ie. racist) comedy of the role with steady integrity, allowing Mammy to be funny not simply because she's a black maid but because she's Mammy, an often amusing person who happens also to be a black maid.

McDaniel is a gifted comedienne, familiar with the bits and the shticks that made blackness funny in 1930s Hollywood, and she utilizes those skills with acuity as Mammy. McDaniel's Mammy and Gable's Rhett Butler are the only characters in the film capable of making fun of Leigh's Scarlett, and their loving mockery helps to lighten the often overwrought film. McDaniel maneuvers the utterly conventional (ie. racist) comedy of the role with steady integrity, allowing Mammy to be funny not simply because she's a black maid but because she's Mammy, an often amusing person who happens also to be a black maid. McDaniel holds presence in this utterly stock character with a nuanced integrity that's fairly astonishing to behold. She doesn't dismantle the stereotype but she does inhabit it knowingly.

McDaniel holds presence in this utterly stock character with a nuanced integrity that's fairly astonishing to behold. She doesn't dismantle the stereotype but she does inhabit it knowingly. McDaniel performs the role of Mammy without apology and, in so doing, she permits the personhood of the character to be revealed.

McDaniel performs the role of Mammy without apology and, in so doing, she permits the personhood of the character to be revealed. Hattie McDaniel's performance is neither defined by or in defiance of the minstrel mask. And this is why, I suspect, the character's final scenes are so fundamentally moving. When McDaniel's Mammy reaches out to Melanie for help in ministering to her grieving employers, she does so with visible, powerful feeling. She's more emotionally raw than anything we've seen before. Yet what impresses me here is that it's the same Mammy. McDaniel is not finally sharing some secret authentic Mammy "behind the smile," some other "private" Mammy we've not seen before. Rather, Mammy's deeply personal feelings are but another facet of the same woman we've come to depend on, for narrative clarity and comic relief, over the previous four hours.

Hattie McDaniel's performance is neither defined by or in defiance of the minstrel mask. And this is why, I suspect, the character's final scenes are so fundamentally moving. When McDaniel's Mammy reaches out to Melanie for help in ministering to her grieving employers, she does so with visible, powerful feeling. She's more emotionally raw than anything we've seen before. Yet what impresses me here is that it's the same Mammy. McDaniel is not finally sharing some secret authentic Mammy "behind the smile," some other "private" Mammy we've not seen before. Rather, Mammy's deeply personal feelings are but another facet of the same woman we've come to depend on, for narrative clarity and comic relief, over the previous four hours. McDaniel offers an elemental, unguarded performance of this stock character, using the character of Mammy to affirm the personhood of the enslaved domestic. As garish as McDaniel's Mammy might at times seem to contemporary eyes, I would submit that McDaniel's characterization actually stands as a quietly radical gesture which (even though it likely secured the dominance of the "Mammy" stock character as a "good" stereotype for the subsequent century) marks a substantial accomplishment. McDaniel's performance as Mammy is work worth remembering and work worth taking seriously.

McDaniel offers an elemental, unguarded performance of this stock character, using the character of Mammy to affirm the personhood of the enslaved domestic. As garish as McDaniel's Mammy might at times seem to contemporary eyes, I would submit that McDaniel's characterization actually stands as a quietly radical gesture which (even though it likely secured the dominance of the "Mammy" stock character as a "good" stereotype for the subsequent century) marks a substantial accomplishment. McDaniel's performance as Mammy is work worth remembering and work worth taking seriously.

6 comments:

A great write up of one of my favourite winners of this award. Totally awesome!

Can't wait to see your thoughts of DeHavilland.

Like you mentioned, one of my favorite things about this performance is that McDaniel goes places no "black servant" role 20 years before or after ever dreamed of. She's more than just the amusing, lazy maid who does more wisecracking than housework; McDaniel's Mammy has depth far beyond the stereotyped role.

I wonder if the filmmakers even intended for this character to have an existence outside of the domestic role, or whether she was indeed supposed to be simple comic relief. If the latter is true, congrats, Hattie, for going against the grain.

I'd be interested to know what you think of Butterfly McQueen, the actress playing the hysterical other Black maid here ("I don't know about birthin' no babies!") who subsequently refused to play any more maids (and alas, didn't play for much longer in Hollywood). She has a great supporting turn in Cabin in the Sky as well, which I just recently saw.

Oh yes -- and congrats on finally making through this one! :)

Bravo! Just the kind of thoughtful and eloquent examination that McDaniel's work merits - but seldom gets. A lovely tribute to a marvelous artist.

I can recall watching that last scene in which Mammy reveals the marital problems of the Butlers and could easily see why Hattie McDaniel won that Oscar.

Post a Comment