Between this week's and last week's nominated performance, I find that I'm torn. Not necessarily between who I want to win (though that too) but over whether I feel last's week's performance was the "perfect scale" (in terms of screentime/percentage) for a Best Supporting Actress, or whether this week's is. Indeed, this week's profiled performance has been widely considered "too small" or having "negligible screentime" to be a real contender for this year's trophy. And, to put it simplest terms, I couldn't disagree more. The more I do this "Supporting Actress" project, the more I find myself enamored of performances in the 10-15 minute zone, wherein the performer is able to knock my socks off with presence and precision even as they craft a vivid, emotionally potent characterization within a concentrated span of scenes. Indeed, I'm increasingly convinced that such performances display the artistry of supporting actressness at its most sublime height. And, of course, I could likely find no more perfect an example of this premise than this week's nominated performance...

Between this week's and last week's nominated performance, I find that I'm torn. Not necessarily between who I want to win (though that too) but over whether I feel last's week's performance was the "perfect scale" (in terms of screentime/percentage) for a Best Supporting Actress, or whether this week's is. Indeed, this week's profiled performance has been widely considered "too small" or having "negligible screentime" to be a real contender for this year's trophy. And, to put it simplest terms, I couldn't disagree more. The more I do this "Supporting Actress" project, the more I find myself enamored of performances in the 10-15 minute zone, wherein the performer is able to knock my socks off with presence and precision even as they craft a vivid, emotionally potent characterization within a concentrated span of scenes. Indeed, I'm increasingly convinced that such performances display the artistry of supporting actressness at its most sublime height. And, of course, I could likely find no more perfect an example of this premise than this week's nominated performance...

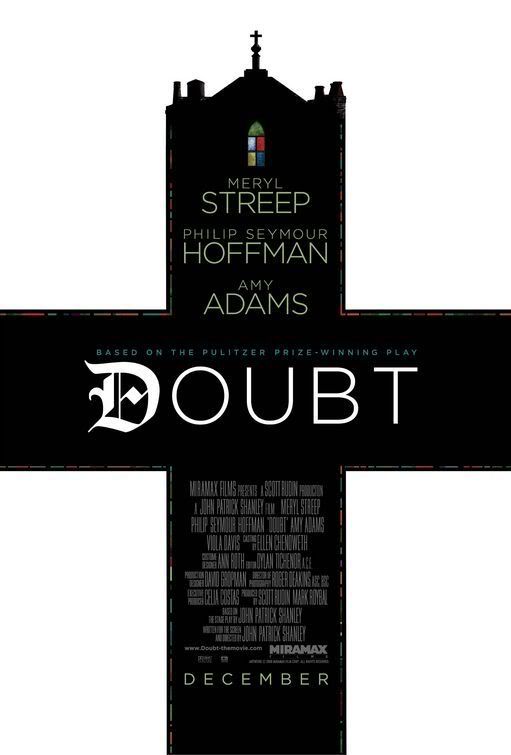

...Viola Davis in Doubt (2008)

approximately 10 minutes and 41 seconds

3 scenes

roughly 10% of film's total running time

In the film, Meryl Streep's Sister Aloysius and Philip Seymour Hoffman's Father Flynn are steeped in a fearsome contest -- a dogfight in clerical garb, really -- between certitude and doubt, between viciousness and veracity. Writer/director John Patrick Shanley amplifies the dramatic intensity of his elegantly algebraic "he-said-she-said" conceit by factoring in an unknowable variable; we are never told what "really" happened and, as such, must contend with the unverifiability of our own beliefs about the events unfolding within this play and (by extension, one presumes) the world at large. By the time Davis's Mrs. Miller appears, however, the film's narrative action has been framed as a classic, zero-sum game pitching protagonist against antagonist. (Who the hero or villain might be -- Aloysius or Flynn -- is cannily left to the audience to decide.) And, at first, Mrs. Miller's arrival promises to tip the battle in favor of one contender.

In the film, Meryl Streep's Sister Aloysius and Philip Seymour Hoffman's Father Flynn are steeped in a fearsome contest -- a dogfight in clerical garb, really -- between certitude and doubt, between viciousness and veracity. Writer/director John Patrick Shanley amplifies the dramatic intensity of his elegantly algebraic "he-said-she-said" conceit by factoring in an unknowable variable; we are never told what "really" happened and, as such, must contend with the unverifiability of our own beliefs about the events unfolding within this play and (by extension, one presumes) the world at large. By the time Davis's Mrs. Miller appears, however, the film's narrative action has been framed as a classic, zero-sum game pitching protagonist against antagonist. (Who the hero or villain might be -- Aloysius or Flynn -- is cannily left to the audience to decide.) And, at first, Mrs. Miller's arrival promises to tip the battle in favor of one contender. Streep's Sister Aloysius uses her status as principal of the school where Mrs. Miller's son is the first and as yet only black student as pretext to have a one-on-one conversation with the boy's mother about the possibly "inappropriate" relationship the boy has developed with Hoffman's Father Flynn.

Streep's Sister Aloysius uses her status as principal of the school where Mrs. Miller's son is the first and as yet only black student as pretext to have a one-on-one conversation with the boy's mother about the possibly "inappropriate" relationship the boy has developed with Hoffman's Father Flynn. As Davis's scene with Streep begins, Mrs. Miller knows none of the priest-nun politics that have compelled her visit to the principal's office. And as the conversation between the two women begins, Davis allows haunting uncertainties and anxieties to flit across Mrs. Miller's face as the character struggles to find her footing in this unexpectedly forthright encounter with Aloysius, a white woman with a title, a habit and a measure of power.

As Davis's scene with Streep begins, Mrs. Miller knows none of the priest-nun politics that have compelled her visit to the principal's office. And as the conversation between the two women begins, Davis allows haunting uncertainties and anxieties to flit across Mrs. Miller's face as the character struggles to find her footing in this unexpectedly forthright encounter with Aloysius, a white woman with a title, a habit and a measure of power. At first, Davis's Mrs. Miller appears single-mindedly concerned with whether or not her son Donald has done anything to trouble his continued enrollment at Sister Aloysius's school.

At first, Davis's Mrs. Miller appears single-mindedly concerned with whether or not her son Donald has done anything to trouble his continued enrollment at Sister Aloysius's school. The role of Mrs. Miller is a device, certainly. She's introduced in a fashion not unlike that befitting a surprise 3rd-act witness, the one with damning testimony sure to seal the trial's outcome. Yet what Mrs. Miller actually delivers is an even greater surprise, one that threatens to shock Sister Aloysius's foundations more than anything else.

The role of Mrs. Miller is a device, certainly. She's introduced in a fashion not unlike that befitting a surprise 3rd-act witness, the one with damning testimony sure to seal the trial's outcome. Yet what Mrs. Miller actually delivers is an even greater surprise, one that threatens to shock Sister Aloysius's foundations more than anything else. In an illuminating rendering of Shanley's script, Viola Davis crafts Mrs. Miller as a woman for whom at least two things are true.

In an illuminating rendering of Shanley's script, Viola Davis crafts Mrs. Miller as a woman for whom at least two things are true. First, Davis conveys that Mrs. Miller loves her son with a fierce passion and that she has pinned her hopes for her son's future happiness upon his being successful in the best school possible.

First, Davis conveys that Mrs. Miller loves her son with a fierce passion and that she has pinned her hopes for her son's future happiness upon his being successful in the best school possible. Second, Davis communicates -- with a surprising clarity, given the oblique way her character expresses herself -- that Mrs. Miller understands that her son's path toward happiness and success will oblige some, possibly heartbreaking, degree of compromise.

Second, Davis communicates -- with a surprising clarity, given the oblique way her character expresses herself -- that Mrs. Miller understands that her son's path toward happiness and success will oblige some, possibly heartbreaking, degree of compromise. Manuevering these two truths, Davis palpably conveys both the terrifying sense of risk felt by any mother of a black child approaching adulthood in the United States (especially in the early 1960s) and also the incredible specificity of this mother's particular challenge in loving this particular son.

Manuevering these two truths, Davis palpably conveys both the terrifying sense of risk felt by any mother of a black child approaching adulthood in the United States (especially in the early 1960s) and also the incredible specificity of this mother's particular challenge in loving this particular son. Shanley's dialogue scripts an awesome, distilled volley of emotion and information between Mrs. Miller and Sister Aloysius, each woman obliged by social convention to a certain degree of deference even as both are fueled by defiant passion. And it's undeniably thrilling to watch Streep and Davis perform the acting equivalent of an arm-wrestling match, and to see Davis's Mrs. Miller -- slowly, steadfastly -- force Streep's Sister Aloysius to admit defeat. (As you certainly know, lovely reader, watching female actors do their thing is my favorite spectator sport and this scene is like sitting courtside for a late round at an all-star tournament.)

Shanley's dialogue scripts an awesome, distilled volley of emotion and information between Mrs. Miller and Sister Aloysius, each woman obliged by social convention to a certain degree of deference even as both are fueled by defiant passion. And it's undeniably thrilling to watch Streep and Davis perform the acting equivalent of an arm-wrestling match, and to see Davis's Mrs. Miller -- slowly, steadfastly -- force Streep's Sister Aloysius to admit defeat. (As you certainly know, lovely reader, watching female actors do their thing is my favorite spectator sport and this scene is like sitting courtside for a late round at an all-star tournament.) But what I think I so admire about Viola Davis is that she accomplishes something else besides (a) showing Mrs. Miller's ability to defend her child in whatever way she deems fit and (b) demonstrating the actress's capacity to hold her own against the gale force of Meryl Streep in the role of Sister Aloysius.

But what I think I so admire about Viola Davis is that she accomplishes something else besides (a) showing Mrs. Miller's ability to defend her child in whatever way she deems fit and (b) demonstrating the actress's capacity to hold her own against the gale force of Meryl Streep in the role of Sister Aloysius. Davis anchors all the actorly pyrotechnics in a precise character study of this moment as a life-changer for Mrs. Miller. Like the best one-scene or two-scene wonders, Davis amplifies her comparatively small amount of screen time into a precise character study of a watershed moment in Mrs. Miller's life. By the end of her encounter with Sister Aloysius, Davis's Mrs. Miller has discovered the principle that will guide her as she continues to parent her son: she will stand with those who stand with her son. Mrs. Miller probably knew some version of this truth before this moment but Davis, by doing what great actors so astutely do, charts Mrs. Miller's epiphanic realization with emotional clarity and precision, so that we might share in its discovery.

Davis anchors all the actorly pyrotechnics in a precise character study of this moment as a life-changer for Mrs. Miller. Like the best one-scene or two-scene wonders, Davis amplifies her comparatively small amount of screen time into a precise character study of a watershed moment in Mrs. Miller's life. By the end of her encounter with Sister Aloysius, Davis's Mrs. Miller has discovered the principle that will guide her as she continues to parent her son: she will stand with those who stand with her son. Mrs. Miller probably knew some version of this truth before this moment but Davis, by doing what great actors so astutely do, charts Mrs. Miller's epiphanic realization with emotional clarity and precision, so that we might share in its discovery. Viola Davis's work in the role of Mrs. Miller is indelible and elevating, a breakthrough performance for a clearly formidable acting talent. Now let's hope -- against hope -- that Hollywood proves as willing as LaStreep to parry with the remarkable Viola Davis.

Viola Davis's work in the role of Mrs. Miller is indelible and elevating, a breakthrough performance for a clearly formidable acting talent. Now let's hope -- against hope -- that Hollywood proves as willing as LaStreep to parry with the remarkable Viola Davis.

5 comments:

In any other year, I would have no hesitation in giving Davis the trophy. But, she's pitted against Cruz here. It just reminds me how strong the field is this year. Even the weakest nominee is hardly one I can root against, because the actress is so damn likeable. Awesome write-up of such a detailed and forceful performance by an always improving actress.

I have a lot of problems with the way in which Shanley's anachronistic dramaturgy makes this performance a lot more rote than it really is. My thoughts here.

I don't think she held her own in that scene...I think she took it.

Go Viola.

AMEN! In my books, she takes it.

Excellent analysis of an amazing scene -- thanks.

Post a Comment