The third Supporting Actress Sunday for 1961 brings StinkyLulu's attention to a piece with which Lu has a peculiarly personal history,

The Children's Hour, Lillian Hellman's enduring piece about two teachers being accused of -- gasp -- lesbianism. See, in high school, Lulu acted a production of the play (no drag involved so guess which part). And then, the very first thing StinkyLulu ever directed in college was a scene from this play -- the one in Act2 where evil little Mary makes the allegation to her grandmother Mrs. Tilford -- and guess who played Mary

brilliantly in that little freshman acting scene?

A certain one hit wonder... Uh huh. No lie.) There's much to loathe about Hellman's most frequently produced play, yet somehow Lulu remains strangely attached to

The Children's Hour.

But even then, with all this previous exposure, Lulu certainly did not expect to be completely engrossed by...

approximately 26 minutes and 50 seconds8 scenesroughly 25% of film's total running time

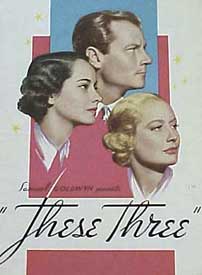

(data courtesy of Raybee) William Wyler's 1961 film is not Hollywood's only adaptation of Lillian Hellman's 1934 play. A

quarter century earlier, Wyler himself directed a sanitized/heterosexualized version of the piece, retitled

These Three, which premiered in 1936. While

the backstory of These Three is interesting, it's most notable for Supporting Actress Sundays to note that Miriam Hopkins -- who, in 1961, is great as Martha's wacky aunt Lily Mortar -- played Martha Dobie in Wyler's 1936 version, opposite Merle Oberon as Karen

and Bonita Granville (who

the Smackdowners saw in 1942's

Now, Voyager) as Mary. By the early 1950s, though, the red-scare and HUAC hearings reactivated an interest in Hellman's play as a theatrical treatment of the power of insinuation and innuendo to ruin lives. Indeed, it's not uncommon to hear

The Children's Hour lumped with Arthur Miller's

The Crucible as "reactions" to McCarthyism, even though Hellman wrote her play nearly 20 years earlier and based it on an essay she read in a 1930 "true crime" anthology (about an 1809 Scottish scandal). The storied 1952 Broadway revival of the play (starring Kim Hunter and Patricia Neal in the lead roles) certainly fueled the piece's contemporaneity and notoriety in the 1950s but, for a variety of reasons, it took Wyler nearly a decade to bring his new cinematic treatment of the piece to the screen.

And it's just like a director like

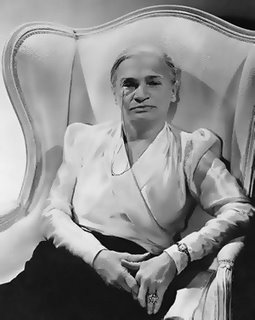

William Wyler to bring a trouper back to the screen in the lynchpin role of Amelia Tilford, the wealthy matron who righteously remakes a child's whispered innuendo into the scandalous allegation that destroys three lives. For this essential role, William Wyler smartly turned to Fay Bainter, who he directed to Oscar in 1938's

Jezebel.

On first glance, and like fellow Class of '61 nominee

Una Merkel, Fay Bainter's nomination might well be understood as one of those "tribute" nominations for which Oscar's somewhat notorious: the kind where the voters give a nod to the work of a performer whose career reaches wayway

back in movie history. Not that Bainter was unworthy of such a tribute. An established early 20th century theatre star (she was a "privileged" member of David Belasco's company in the 1910s), Hollywood snagged Bainter in the early sound era and she quickly emerged as one of the most reliable character actors of the 1930s. For those less interested in

Fay Bainter trivia than in Oscar's minutiae, Bainter's also an important footnote in Oscar history for being

first performer to be nominated both leading and supporting acting categories in the same year (

'38);

only ten performers have been so honored -- Bainter in '38, previous Smackdown subject Teresa Wright '42, Barry Fitzgerald '44; Jessica Lange '82, Sigourney Weaver '88; Al Pacino '92; Holly Hunter & Emma Thompson '93; Julianne Moore '02; and Jamie Foxx '04). Bainter might also blip across Oscar-fiend minds as the

presenter of Hattie McDaniel's historic win in 1939. A reliable film presence in the 1930s and '40s, Bainter worked mostly in television in the 1950s. 1961's

The Children's Hour marked both Bainter's return to film as well as her final film performance, a swan song of sorts for

seven decades of thespianism. (Bainter died in April 1968, about six years after the 1961 Oscar ceremony.)

The character of Amelia Tilford might easily be misrecognized simply as the villain of the piece. But neither Wyler nor Fay Bainter make that mistake. Bainter's performance is -- in a very subtle way -- perfectly electrifying. When she walks into the room, everyone seems to stand at attention, a curious power that both Wyler and Bainter expertly deploy in service of the character. Swathed in the garb of a meticulously genteel dowager, the outfits barely disguise the ferocious lionness underneath. Mrs. Tilford's furious instinct to protect her grandchild rages in Bainter's eyes. Bainter smartly plays Mrs. Tilford as a not unkind woman -- just a little too sure of what she thinks she knows -- and whatever villainy follows stems from this misguided righteousness. Mrs. Tilford's problem comes first when she places her cultivated confidence as surety for a petty child's insinuation, and next when the devastating impact of her actions are impervious to her amends.

Bainter's most complex moment comes when her granddaughter Mary's selfish trickery and malicious deception are finally revealed. Rosalie -- Mary's little klepto minion (played very well here by the always delicious

Veronica Cartwright, when she was maybe

11) -- has just come clean, telling Mrs. Tilford that Mary forced Rosalie to verify Mary's lies about their former teachers. Just then, Mary (played atrociously by

a little beast in her single film role) stomps into the house. Bainter's Tilford demands that she "come here." Frozen still on the stair, Mary sees Rosalie, figures what's happening and begins to protest, but the glare Bainter's Tilford gives her beloved, monstrous granddaughter? It just burns the screen; the genteel old lady is pissed and Mary's gonna get it (

nyahnyahnananyah). But right then -- as though the karmic boomerang of righteousness just swoops back and clips her smack in the back of her knees -- Bainter's Tilford buckles and falls to the floor. As she refuses assistance to stand, it's clear:

This moment -- not the many good deeds that came before -- will be the defining moment of Amelia Tilford's life and legacy, and that realization seems to age the woman before our eyes. It's deep, this scene -- and Bainter and Wyler pitch the tone of it perfectly. Revelatory without being redemptive, Bainter's Mrs. Tilford emodies the reciprocal damage of deception and Tilford's pathetic and fruitless attempts to make amends for her actions become -- for better and worse -- the most haunting of the myriad tragedies and losses scripted in this narrative.

In a film with powerful performances from James Garner and Shirley Maclaine, with what is -- arguably -- Audrey Hepburn's most textured performance, Fay Bainter's work in this role -- while not necessarily trophy worthy -- is certainly nomination worthy...one of the handful of "tribute" nominations that withstand this Oscar-dork's scrutiny. StinkyLulu's pleased that this nomination served as a powerful re/introduction to Fay Bainter. That's what Lulu so loves about Supporting Actress Sundays: the opportunity to give full attention to brilliant actressing at the edges...like Fay Bainter's performance in

The Children's Hour.

One of the challenges routinely faced by actresses at the edges, especially in genre dramas, is portraying what I've come to think of as a "collateral damage" character -- a figure designed to underscore the fundamentally tragic consequences of the core moral/narrative conceit. Usually, the "collateral damage" character is that gal who knows that little bit too much (think of Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street or Sylvia Miles in Farewell, My Lovely) but just as often such a character is the innocent fawn disastrously ensnared in a complicated dramatic web well beyond her, like Penelope Milford in Coming Home or...

One of the challenges routinely faced by actresses at the edges, especially in genre dramas, is portraying what I've come to think of as a "collateral damage" character -- a figure designed to underscore the fundamentally tragic consequences of the core moral/narrative conceit. Usually, the "collateral damage" character is that gal who knows that little bit too much (think of Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street or Sylvia Miles in Farewell, My Lovely) but just as often such a character is the innocent fawn disastrously ensnared in a complicated dramatic web well beyond her, like Penelope Milford in Coming Home or...